How America Could've Avoided its Impending Debt Catastrophe

A single Republican senator's vote thirty years ago would have stopped America's debt bomb from ever forming

The day was March 2, 1995.

Four months prior, the Republican Party had triumphed, taking 54 House and 8 Senate seats from the Democrats (plus another from Richard Shelby’s post-election switch), completing their first congressional takeover in 42 years.

Key to that victory was the Contract with America, written by Newt Gingrich and Dick Armey, which articulated a simple populist agenda that the party pledged to enact once in power. The first item in the Contract was a pledge that within 100 days of the beginning of the 104th Congress, the Fiscal Responsibility Act would be proposed and debated. This act would include “A balanced budget/tax limitation amendment and a legislative line-item veto to restore fiscal responsibility to an out-of-control Congress, requiring them to live under the same budget constraints as families and businesses.”

It worked, and after the new majority was sworn in, they quickly got to work trying to implement that agenda. The first and most important item in the Contract — the Balanced Budget Amendment — took center stage early on.

The Balanced Budget Amendment

The seven sections of the proposed amendment in House Joint Resolution 1 were relatively straightforward. If passed by Congress and ratified by the states, it would mandate that the Federal government maintain a budget in balance after FY 2002, while limiting the authority of Congress to increase the statutory debt limit. It would also provide for needed flexibility by exempting the government from these rules during a time of declared war, or if a three-fifths vote in both houses of Congress deemed it necessary.

In the mid-1990s, this idea was broadly popular among members of both parties. Years of anxiety over the rise of deficit spending in the Reagan, Bush and early Clinton administrations had built populist support for the idea of constitutionally limiting the ability of politicians to continue to increase debt.

Many Democrats in both the House and the Senate supported the idea of not only balancing the budget but of enshrining the requirement to do so in the Constitution. Despite the Republicans only having 230 members in the House of Representatives, H.J. Res. 1 passed overwhelmingly 300 to 132 — 72 Democrats joined with 228 Republicans voting in favor — comfortably making it past the 290 vote requirement.

This vote filled Republicans with a sense of momentum and a belief that the amendment would pass in the Senate as well. Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole only had 53 Republicans in his caucus at the time and needed to get to 67 affirmative votes, but many prominent Democrats had voiced their support, and Minority Leader Tom Daschle had actually voted for it in 1994.

35 days after the measure passed the House on January 26th, the Senate attempted to follow suit.

Complications in the Senate

Sensing they were close to the votes they needed, the days leading up to the vote had seen furious lobbying by Republicans. Some Democrats had immediately come on board, but prospects were dimmed when President Bill Clinton announced his opposition and Daschle turned away from his previous support, pledging to vote no.

Clinton, ever the Keynesian, claimed to be worried that in times of recession, the amendment would prevent the government from spending money to prop up the economy, possibly tipping the country into depression. Additionally, he felt that it would give too much power to the Federal Reserve, because according to Clinton "when they raise interest rates, they raise the deficit."

Daschle took a far more political line against the amendment. Hungry to deny the Republicans a win and knowing that fear of cutting popular entitlement programs may be able to doom the vote, he began arguing that Social Security would be threatened if the proposal was enacted.

Their argument went a little something like this: if the Balanced Budget Amendment began to force the government to make difficult choices on spending, Social Security would end up being cut in order to comply with the Constitution. This, of course, is perhaps the least likely eventuality, but the argument was enough to reinforce shaky members of his caucus.

Daschle repeatedly said that he actually did support the idea of a Balanced Budget Amendment, but wanted to amend it to insert language that would “protect the Social Security Trust Fund.” This, despite the fact that the proposed amendment he voted in favor of one year prior was identical to the 1995 version, and despite his knowledge that there was no workable language that could be inserted.

The strategy worked in turning several Democrats against the amendment, but a significant number of Democrats — 14 in total — were still planning to support the measure. The group included Senators Baucus, Breaux, Bryan, Campbell (who would go on to switch parties, becoming a Republican the following day), Exon, Graham, Harkin, Heflin, Kohl, Moseley-Braun, Nunn, Robb, Simon, and none other than Joe Biden.

Those 14 Democratic Senators, together with the 53 Republicans, would have been just enough to reach the needed threshold of 67 and pass the Balanced Budget Amendment. If they could do that, ratification by the states would have been very likely to follow.

There was just one problem: Republican Senator Mark Hatfield of Oregon.

One Vote

Hatfield, who was chairman of Senate Appropriations Committee at the time, had announced two weeks before the vote that he would not be supporting the amendment. “I cannot in good conscience,” he said, “vote for the amendment [and] forever alter the way our Constitution is interpreted.”

Hatfield was part of the liberal wing of the Republican Party. In the 1980s he sparred with President Ronald Reagan on spending, pushing against Reagan’s defense buildup and instead advocating for more domestic social spending. Key to his opposition to H.J. Res. 1 was a belief that fiscal policy should not be enshrined in the Constitution. He would later say that the effort to pass the Balanced Budget Amendment was nothing more than “a political ploy to erroneously make Americans think [the government was] actually doing something about the deficit.”

While others in the Republican left flank chose to vote in favor, Hatfield refused, making him the only member of his party to oppose the amendment. When he announced his disapproval, it was still believed that the vote could be won without him by gaining enough Democratic votes. But as time went by, it became clear that the Republicans could not prevail if Hatfield failed to support the amendment. In a frantic attempt to save the effort, he was intensely lobbied for days, and yet would not change his vote.

And so on March 2nd, 1995, the best opportunity that America has ever had to force its government to control spending and limit debt died by a single vote.

(Note: The official Senate vote is recorded as 65 to 35 rather than 66 to 34 because Dole switched his vote to no to procedurally allow him to bring the measure up for reconsideration.)

There were other attempts that came close to passage in the 1980s, such as in 1982 when the Senate passed the measure 69 to 31. Unfortunately, in that instance, the House — which was 236 to 187 in favor — was nowhere near the two-thirds majority that was required. There would also be future attempts to pass the amendment, including another single-vote loss in the Senate in 1997 that came after freshman Democrats Tim Johnson and Robert Torricelli reversed their prior support for it in the House.

But none would get as close as the vote in 1995.

Why The Failure Matters

A Balanced Budget Amendment is by no means perfect. It is, at best, a blunt instrument to restrain fiscal irresponsibility. If enacted, it would do nothing to guarantee lower spending or a smaller government. Future presidents and members of Congress could easily make rhetorical use of the amendment to justify higher taxes to maintain Federal largesse, claiming that they had no choice. Furthermore, critics are not necessarily wrong in that it takes away budget flexibility, and could very easily create a new political weapon to be used in bad faith by political actors.

Yet for all its faults, it would have done immense good if passed, and the amendment’s failure in that moment is starting to look tragic. Hatfield single vote in 1995 paved the way for three decades of fiscal mismanagement and an increasing government addiction to debt.

At the time of the debate, America’s outstanding debt stood at about $4.8 trillion. Today that total has exploded to $34.2 trillion, and is on track to surpass $54 trillion by 2034. This has been fueled by uncontrolled and ever-increasing deficits, which have pushed the country into a dangerously high debt-to-GDP ratio:

Opponents of the 1995 bill, including Hatfield, argued that Congress did not need the Balanced Budget Amendment to pass a balanced budget. This is undeniably true, but tends only to become a possibility on the rare occasions when political will emerges, usually forced upon politicians by a demanding electorate that frightens them into financial responsibility.

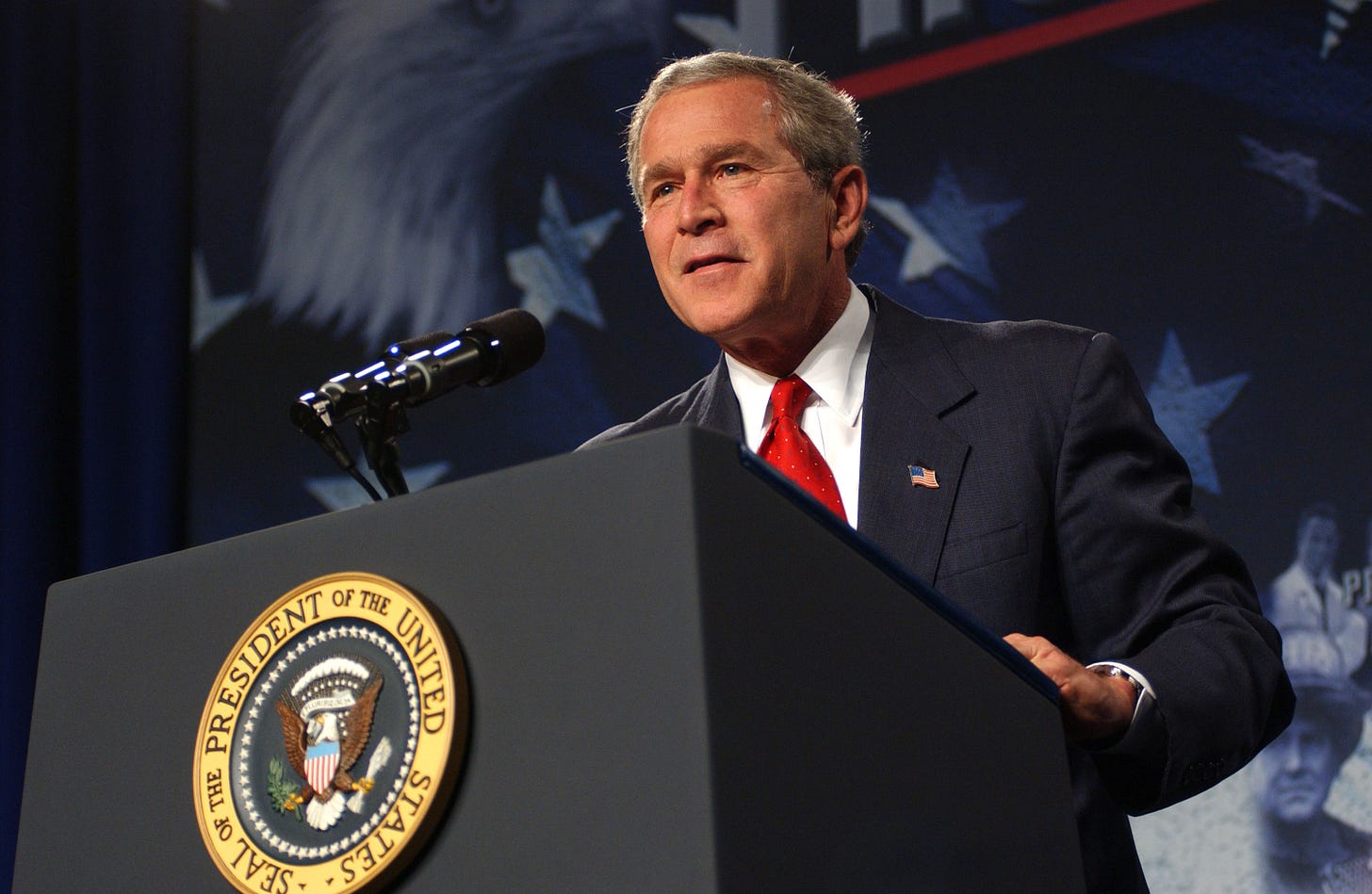

The classic example of this is the pressure that Republicans put on Clinton, who was uniquely willing to collaborate with them and ultimately proposed a balanced budget for the first time in 30 years. Another can be seen in George W. Bush’s second term, when the president and allies in Congress began to walk back the debts incurred — at the insistence of that same group of politicians — during the early 2000s War on Terror. This lowered the deficit from $412.7 billion in FY 2004 to $160.7 billion in FY 2007, before ultimately exploding in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

But relying on these rare — very rare — and temporary bouts of fiscal sanity is naive and ineffective, particularly in the era of bitter partisanship we find ourselves in today. Most of the time irresponsibility reigns supreme because politicians have learned to exploit the perpetual popularity of generous domestic spending, giving the political class a powerful incentive to spend as much as possible by any means available.

That spending is now fueled largely by debt and there is no immediate disincentive, either financially or politically, against its use. Borrowing will give the appearance of additional revenue to use for spending, and any negative consequences that may result from the accumulation of debt will not be felt for years, decades, or longer. This means that there is no reason for a politician of any party to prioritize responsible budgeting.

To solve this, there needs to be some kind of mechanism to force the issue because we will never be able to rely on electing better leaders. Milton Friedman once said, “We shall not correct the state of affairs by electing the right people; we’ve tried that. The right people before they’re elected become the wrong people after they’re elected. The important thing is to make it politically profitable for the wrong people to do the right thing. If it is not politically profitable for the wrong people to do the right thing, the right people will not do the right thing either.”

Friedman was not speaking about a Balanced Budget Amendment at the time, but was instead speaking generally about the necessity of creating political systems that incentivize the wrong people — of which we have plenty in government — to do things that would otherwise be difficult to do. Things like restraining the impulse to spend money with no regard for rising debt.

We have plenty of examples of how this works in practice at the state level. Local politicians are no different than their national cousins, they just play in a smaller sandbox. They face the same temptations to spend, and would — if given a chance — be similarly seduced by the opportunity to pay for that spending by borrowing.

And yet even irresponsible, fiscally imprudent states remain in relative balance each year. How?

Because states have tied the hands of their politicians. Nearly every state in the country has some kind of statutory requirement for balanced budgets, meaning that most governors and state legislatures are legally prohibited from spending more than they collect in revenue.

Put another way: the wrong people have been forced to do the right thing by law.

What Could’ve Been

Had the amendment passed in 1995 and been ratified, FY 2002 would’ve been the first year that the requirement would have been in place. The preceding FY 2001 budget was already $128 billion in surplus, so there would have been no difficulty in complying with the requirements of the amendment.

In the real world, the 2002 budget was submitted in April of 2001 by new President George W. Bush, and was impacted by economic uncertainty due to the dot-com crash, as well as his proposed tax cuts. Bush’s proposal spent $157.7 billion more than it took in, returning the budget to deficit after four years of surplus.

With a Constitutional balance requirement in place, this would not have been an option. Bush and the divided Congress would have needed to figure out a way to equalize revenues and expenditures. However it happened, it would have kept the government from slipping into deficit, and provided a new baseline against which the following year’s budget could be responsibly built.

Instead, we got just the opposite. The deficit ballooned to $412.7 billion by 2004, $1.4 trillion by 2009, and $3.1 trillion by 2020. It has grown in Republican administrations and Democratic administrations, Republican congresses, and Democratic congresses. While there are certainly differences in the behavior of the parties at the periphery, on fiscal issues the reality is that no politician or party has acted responsibly for more than twenty years.

All of that would’ve been different if the Balanced Budget Amendment had been in place, because it would’ve been much easier to maintain a careful equilibrium. Without an enormous hole to dig out of each year — a hole that constantly gets deeper — it would be far easier to get to balance. Over time, this would have prevented America from adding $28 trillion to the debt since 2002.

There are caveats to the optimism. There is no question that the September 11th attacks, the Great Recession, and the COVID-19 pandemic would all have provided opportunities for Congress to invoke the exceptions to the balance requirement. If the Senate can vote 96 to 0 for a $2 trillion Coronavirus relief bill in March of 2020, they shouldn’t have any trouble getting a three-fifths vote to allow temporary deficit spending during a pandemic.

Had that happened, the nation would still have added debt in the last 22 years, just considerably less of it. Even if it was just half as much, the United States would only have about $20 trillion in debt today, as opposed to $34.2 trillion. Even with some additional debt from these special cases, we would still be better off because having now returned to post-emergency governance, the government would be forced to be back in balance today, rather than have a $1.6 trillion yearly deficit, as we do now.

Ultimately, it is hard to see how the country would’ve been any worse off had it passed the Balanced Budget Amendment in 1995, and there is a very good chance it would’ve stopped the debt problem from metastasizing into the financial cancer it has become today.

A blight so bad it almost guarantees a future catastrophe could have been prevented, if not for a single vote in 1995. At the time, Senator Hatfield was hailed as a hero for exhibiting political bravery by telling his own party no.

Today, it is hard to see him as anything other than a short-sighted villain.

Amazing article. I hope younger people would/will read. The impacts of exponential debt increase, among others, will be the end of efforts held dear, like managing climate change.

Friedman was right then... and now.

It is a testament to the greatness of our republic that it can suffer these fools we call leaders... and still, in large part - function.

However, I am no longer encouraged when I look to the future.